I’ve wanted to write about the deeply provocative, complex, ugly, and yet somehow beautiful work of DMX1 for some time, before his death. Mainly, I wanted to write about him because of my mom.

My mother’s favorite rapper is DMX. She’d rap along to his albums, her flow charged, on pace and in time with X’s voice. I grew up hearing his voice roar and rattle off like a machine gun from the surround sound speakers of the living room. On Saturday mornings, when my parents would rise to do chores — DMX was the soundtrack. His music was cranked so loud the walls vibrated.

I suspect there is something about the violent bravado giving way to (or because of) DMX’s raw brokenness, that spoke to my mother. Music is magical in a mysterious way. The way the riffs and drum tap into our most primal urges—the animal, the sexual, the monstrous. How the lyrics can speak directly to us or for us. We are wrecked by music’s transformative powers. My mother always identified with X’s soul-baring rap. She identified with his pain and the inability to forget what hell you traversed and survived. And my mother has gone through her own private hells, hair singed, clothes smoldering — but still standing, with air in her lungs.

Trouble haunted DMX’s life from beginning to end. But what was truly unforgettable about DMX’s artistry was his spirituality, his mysterious faith, his supplication before God. All the while his spirituality also took on the sexist and homophobic tenets of religion. Something he sometimes successfully shook off, but struggled to let go of in its entirety as his music matured.

It still boggles my mind that DMX could release two multi-platinum albums in the postmodern late 20th century, spitting bars that menace and throttle, just to interrupt himself with stripped-down, spoken-word prayers to God. Mind boggling how DMX’s music could be so brutal, and yet imbued with a religious experience which helped him battle demons as long as he did.

“A deal with the dark was one that I had made many times. Whether it was something that I needed to get out of hunger, or something that I wanted to get out of temptation, throughout my life I agreed to do dirt and suffer the consequences.2 - DMX

When X tragically passed away last year, my heart broke for his family and friends, and the millions of fans praying for a miracle. My heart also broke for my mother. Surely, my mother is his biggest fan. And so I’m writing this elegy on her behalf, in praise of the work and iconography of DMX.

Red is the Flesh

1

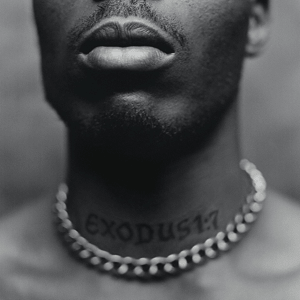

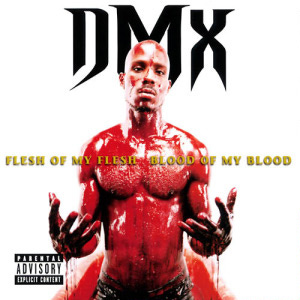

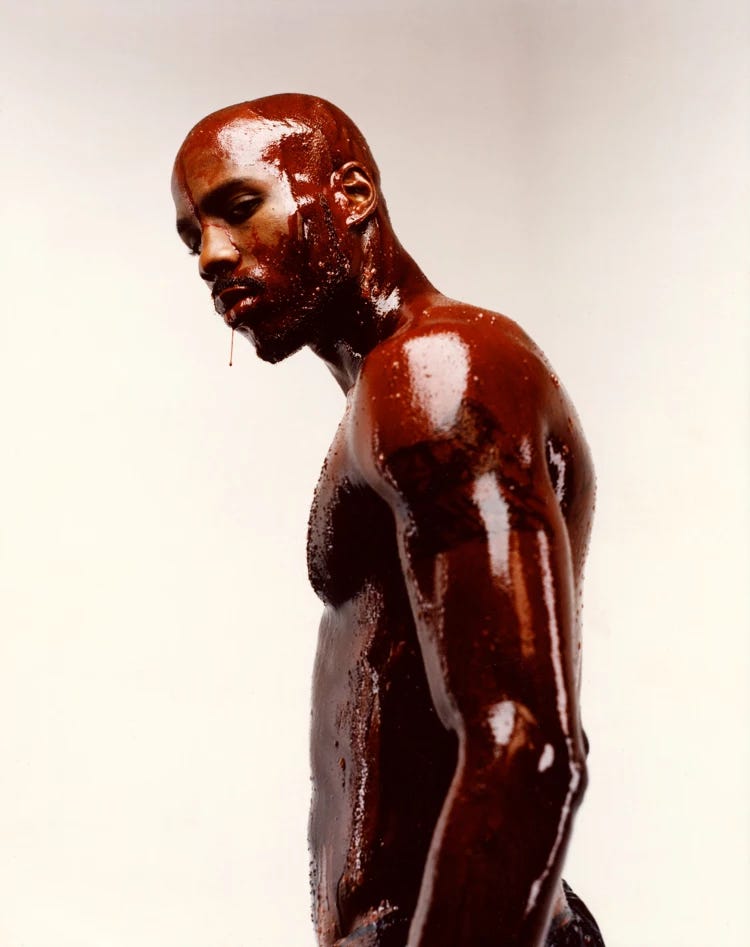

For the better part of X’s prime in the rap game, I remember him not just wearing red, but performing the color red. To me, he embodied it. His skin drenched in red on the cover of Flesh, as if baptized in so much blood that he could never wash it from his face, his hands, his chest. Stained. Tainted.

2

The motif of bloodshed is a river whose currents wind around every lyric in DMX’s music. Visceral, he wielded words like a chainsaw shredding anything and anyone, in slugfests like the hits “Get At Me Dog” and “What’s My Name.” For X, the shedding of blood was both precarious and precious. He always had his metaphorical gun trained on a foe’s brow bone. And yet, in between the fire-breathing on his tracks, X was faithfully and calmly resigned to the higher laws of the streets. He understood there was always a scope trained on him as well. An eye for an eye.

When we're starving, we eat whatever's there

Come on, you know the code in the streets: whatever's fair3

But also the bonds of brotherhood and loyalty means blood-for-blood is a precious exercise in love and honor. His voice quivering and crying with proclamation and tears, DMX exclaims in “Prayer:”

So, if it takes for me to suffer for my brother to see the light

Give me pain till I die! But, please, Lord, treat him right4

The laying down of one’s life for family, friends, those who can’t defend themselves — and the highest of platonic love in the hood — “my niggas.”

For that nigga I would bleed, give him my right hand.5

3

“Therefore as surely as I live, declares the Sovereign Lord, I will give you over to bloodshed and it will pursue you. Since you did not hate bloodshed, bloodshed will pursue you.”6

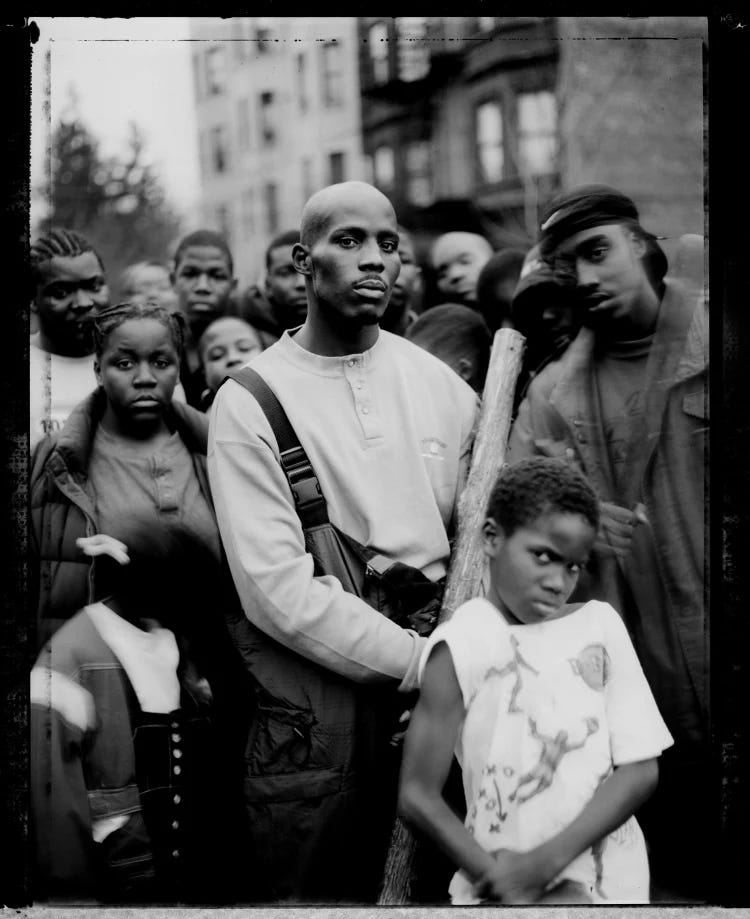

DMX was always down for war, addicted to the battle. X, real name Earl Simmons (born 1970), was starved and beaten by his mother and her various boyfriends. So badly sometimes he sustained wounds and bruises, lost teeth. Abused, often tricked and betrayed by the adults who were supposed to protect him, as a child, Earl was given over to liquor and drugs (which began a lifelong struggle with addiction). He learned to fend for himself at children’s homes and the streets of Yonkers, NY. He committed arson, strong-arm robberies, car-jackings. He saw the inside of prison cells.

I don’t mean to suggest that DMX was senselessly violent — despite what the bite of his raps would tell listeners. I mean to suggest that violence colored young Earl’s world early and often. His psyche developed around the contours of violence. His mind and heart, malnourished and searching, could easily understand the inherent logic in violence.

“Suffering was DMX’s cross to bear, and his darkest instincts endlessly threatened to overrun his road to healing, so he excelled at the art of suffering.”

- Clover Hope, “How DMX Found God,” Pitchfork

Before fame, violence (and all that it entails: drug dealing, stealing, etc.) was how Earl fed and clothed himself, how he stayed alive in cities indifferent towards his and other Black men’s physical, mental, and social suffering. I often re-read and misread DMX’s lyrics and iconography in pursuit of answering whether DMX loved violence. Yes, his lyrics delight in the defeat and punishment of his enemies, but I believe X had a sobering philosophy on bloodshed: life is hell; one must battle the flames with more flames.

When the world — an unjust, unruly society — lusts after your blood, you must make the world bleed in turn. X did not love violence, but he certainly condoned it. Especially violence as a means of rescue—not only to save himself, but the fight to save his sisters and brothers in the hood. Whether we like it or not, and we often like it if our long suffering heroes face the world with meekness, a brutal, nihilistically pragmatic mentality helped get Earl to the next meal, to the next shelter, and ultimately to the next opportunity to make music. Violence birthed DMX.

4

A riot is the language of the unheard.7 Bloodshed is the language of those fighting for agency, for voice, for salvation. DMX had a riotous nature, something natural to his spirit since birth, but cultivated by the twin devils of abuse and poverty. I argue that violence is a language everyone, regardless of class, race, and gender, can understand even if they do not speak it fluently. The better your standing is in life, the more you purposefully fail to comprehend the true nature of violence born of helplessness. The American educated class little understand the violence born out on the Black streets of New York City or Los Angeles or Chicago. Violence, a tolerance of bloodshed, is a symptom of historical societal injuries, such as neglecting Black children in school, undermining Black enterprise, and plunging Black communities into generational poverty across the U.S. DMX’s music is a product of such injustices. In Western critique, art born out of the experience of violence, whose artist is Black or Brown, is often misunderstood or unfairly criticized or neglected in philosophical observation— in comparison to white or European artists.

5

English film director Derek Jarman8 said, “Red protects itself. No color is as territorial. It stakes a claim, is on the alert against the spectrum.” I suspect this is why DMX was drawn to the color as one of many symbols of his artistic persona. Not simply because of DMX’s poetic preoccupations with blood, warfare, and aggression, but because red does not hide.

When I relay “takes up space,” I mean that the color asserts its vibrant dynamism, it fills up every inch of the environment in which it finds itself caged. And yet red warns that it cannot be contained. Red is a wild, stray dog, snapping his jaws around a bone. The color red presents itself like a heavy, metallic, thick shield.

6

Imagine grasping the power and security of this color as a traumatized young man, running the streets, and coming into his own as a DJ, and then a rapper. DMX saw the color red as a keen embodiment of his artistic output because red cannot be missed, glowing hot with dangerous power. But also, red is the color of courage. Fearlessness, endurance, and sacrifice being consistent motifs in DMX’s lyrics.

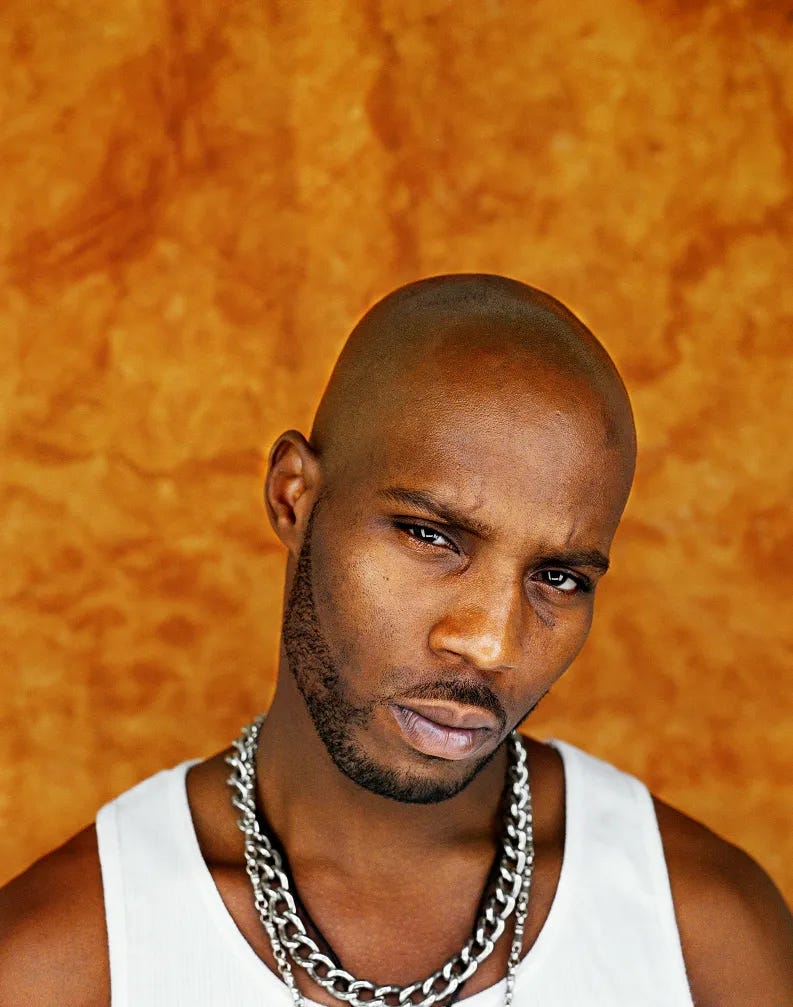

Remember the command at which DMX gripped a crowd of thousands at Woodstock ‘99. He battled the beat, sweating and barking, to a crowd who hungered for his brutal rhymes, who he had full control of despite the chaos of the festival. There DMX was, alone but for a DJ scratching records, on one of the hottest stages of the late nineties, at the height of his powers, in blood red overalls and maroon Timberland boots. His red wardrobe is like a beacon saying look at my sweat and blood, which I shed for the love of the rap game. See my courage. My sacrifices command your attention, deserve space.

7

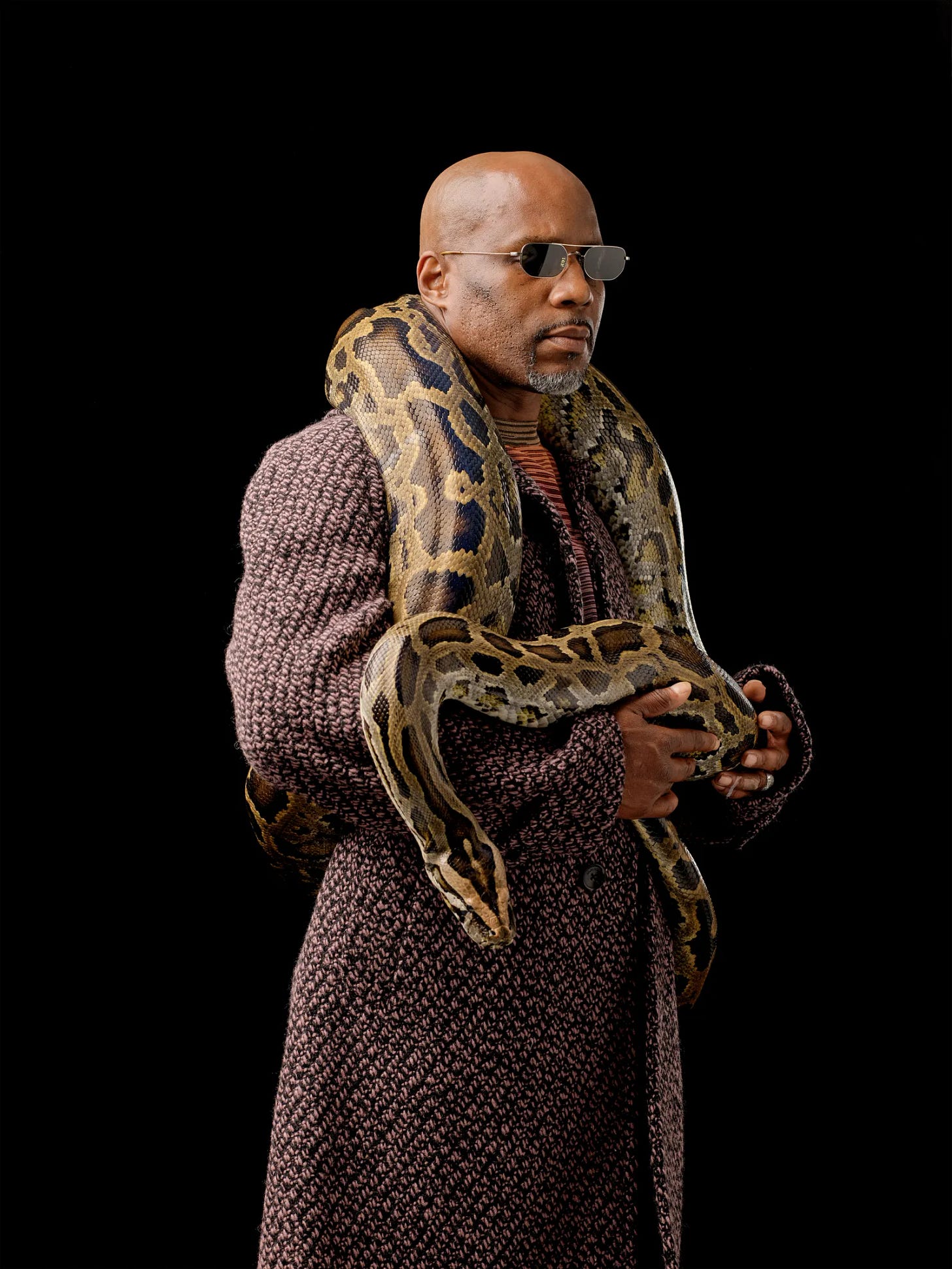

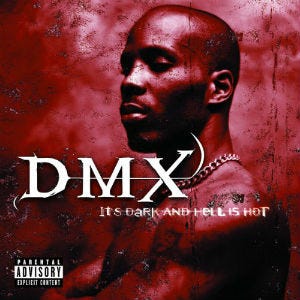

X’s debut album in 1998, It’s Dark and Hell is Hot, and the follow-up, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood are twin flames. To experience the two albums, released within seven months of each other is akin to being trapped inside the screeching, grinding speakers of a headbanger’s ball. Which is also center stage at a bloody, ancient war ritual in which Black men hammer at drums and dance. Which is also a religious experience.

An unflinching double opus.

In 2015, Pitchfork Magazine reflected on the power of X’s debut, calling it, “The Dante’s Inferno of rap.” Lyrically, sonically, the albums plunge us into a Hell populated by the voiceless, fighting and clawing to be seen, to get revenge, to return to the living, and thrive. Hellhounds are constantly barking, and upon first listen, you are shocked to know those very howls and growls are coming from DMX himself. These albums sound red.

Visually, Hell’s album artwork depicts DMX in the underworld. The entirety of his torso is cloaked with the deepest, richest shade. His skin is fiery red, as is the background. He crosses his arms and with a defiant half-turned look, almost a bored look, peers out from his hellish dungeo. Breaking the fourth wall, he glares at us. But also, his eyelids are low, almost heavy. Is he really looking at us? His eyes appear to be closing, as if a calm has washed over him, a meditative embrace of Hell.

But he is master of this wretched space, not a prisoner. On the cover of Hell, X is not baring his teeth like the pitbull his iconography worships, nor does this cover truly reflect the sonic rap pandemonium of the album itself. Except, DMX, ruddy-skinned, consumed by fire and raining blood, on the cover, embodies a quiet, but haunted resignation to his fate.

8

For all the hell-raising that DMX does on his debut album, there are tender, meditative moments. Critics of DMX’s output find it difficult to reconcile that, in practice, X is both tortured and at peace. How do both exist at once in one man? And yet, I find this paradox to be in concert with the humanness of DMX’s unique blend of nihilism and God-fearing.

When you shine, it’s gon’ be a sight to behold.9

Pursued by bloodshed, DMX’s music represents a man no longer vexed by violence, understanding the indiscriminate absurdity of the human experience. Historically, humanity operates on such paradoxical concepts: human behavior that both affirms life and opposes it, that generally accepts the concept of objective truth, and yet cannot confirm it. And like the color red, DMX, passionate and raging, pursues all of these threads of contradiction in his music. Reconciling this nihilism led DMX to God, to answer a spiritual call. Its voice clear, and yet obscured by the static of embodied trauma. The only thing DMX feared was God, even as Death chased X until his final breath.

DMX acutely defined suffering, made suffering not only an artform, but a condition of his Christianity. To suffer was often to be in the presence of God. At the very core of suffering is the question “why?” Why is what DMX asked God constantly, as evidenced by a number of songs across his catalog (“Prayer” and “Damien” from Hell; “Slippin’” from Flesh; “Lord Give Me a Sign”). Why did God choose him to bear this cross, to carry the trauma he faced? And why, after all the destruction left behind in his wake, was X anointed a child of God?

“After a show on the pioneering Hard Knock Life arena tour in 1999, he questioned his good fortune: As producer Irv Gotti once recalled in an interview, X broke down backstage after performing and screamed, ‘Why, why God, why me? I ain’t supposed to be shit.’”

-Clover Hope, “How DMX Found God,” Pitchfork

9

Photographer Jonathan Mannion recalls on the album cover shoot for DMX’s sophomore album, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood: “I had 60 gallons of blood in a bathtub and I was like, ‘Now my challenge is getting DMX in this blood and what am I gonna do to get him in there.’”10 To learn that X was hesitant (apparently worried about destroying his new pants) is shocking. The confidence, the control in which he is depicted on the cover of Flesh, covered head-to-toe in “blood,” does not betray a man who was fearful. Mannion has his suspicions as to why X was hesitant. Was it really for fear of ruining designer pants, when X had over a dozen extra pants on standby? Was it gross to get in a tub full of chocolate syrup? Sure. We won’t really understand the hesitancy, but Mannion and X produced the most iconic image of the rapper in his entire career.

Mannion as a visual artist understood DMX’s iconography is about flesh and blood. He studied color theory; pursuing how the intensity and fervor of the color red behaved against the background of something neutral and still like the color white. Mannion researched voodoo rituals to investigate the way blood draws our breath in a gasp when we witness it.

There is also the violence of spiritual transformation present in Flesh’s cover. While X, blood dripping from every edge on his body, evokes a warrior having survived slaughter, DMX and other critics grew to understand the cover as a presentation of surrender as well. One can read the cover in two ways: the murderous X calmly showing us his handiwork, having cut down enemies and shook the hood like the Fifth Horseman. Or, is this X in a pose of humility?

Surrender is the destruction of ego and the refusal of godlessness. For X this process was always bloody, wrestling with spiritual and physical demons. The cover evokes X presenting himself before God, covered in his blood, his enemies blood, and the blood of Christ. Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood presents to DMX’s audience that within the music, transformation in all its forms, from a street kid to a rap superstar, from a heathen to a saint, requires sacrifice. DMX believed that sacrifice, denying the appetites of body or weakness of the mind, was always done in pursuit of getting closer to God, reaching for heights of salvation and sanctification a human could achieve during his fleshbound time on Earth.

Throughout his career, but certainly towards the end of his life, DMX spoke openly, in a manner both unabashed and humble, about death.

He had faced down death so many times how could he be afraid anymore? He had been transformed, freed as a survivor of abuse, freed to become the artist he dreamed he could be. By the divine meaning he imbued the symbols of red and blood, DMX embodied them because they invoke the qualities of protection, a metaphorical shield. These elements X needed to not only survive abject poverty and violence — but to thrive. Red, the color of blood, the living liquid that drives us forward in time and space, assures our survival, reminds us that we not only live and breath, but we carry Death in our very veins. DMX was never scared.

Nigga when it’s your time to go, you go11

Sources:

https://time.com/5952926/dmx-legacy-hip-hop/

https://www.wnyc.org/story/remembering-life-rap-icon-dmx/

https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/how-dmx-found-god/

https://bnc.tv/the-life-and-legacy-of-hip-hop-legend-dmx/

https://thewilldowntown.com/the-definition-of-x-life-times-of-hip-hop-icon-dmx/

https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-56647793

https://bodyartguru.com/dmx-tattoos/

https://kidadl.com/quotes/best-red-quotes-about-the-most-passionate-color

https://www.okayplayer.com/originals/dmx-its-dark-and-hell-is-hot-secret-history.html

https://genius.com/a/get-at-me-dog-remembering-the-life-lyrics-legacy-of-dmx

https://owlcation.com/humanities/15-Bible-Verses-on-Blood-with-Meanings-and-Other-Religions

https://www.xxlmag.com/dmx-inspirational-lyrics/

https://www.songmeaningsandfacts.com/ruff-ryders-anthem-by-dmx/

https://www.songmeaningsandfacts.com/dmxs-slippin-lyrics-meaning/

https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/how-dmx-found-god/

https://www.thefader.com/2016/12/04/dmx-flesh-of-my-flesh-oral-history-ruff-ryders

From the rapper’s memoir, E.A.R.L.: The Autobiography of DMX (It Books, 2003), as reported by Clover Hope for Pitchfork Magazine

From the song, “Get At Me Dog” from the album It’s Dark and Hell is Hot

From the song, “Prayer - skit” from the album It’s Dark and Hell is Hot

From the song, “Damien” from the album It’s Dark and Hell is Hot

Ezekiel 35:6 (New International Version)

From the song, “The Convo” from the album It’s Dark and Hell is Hot

Read Jonathan Mannion’s reflections on the Flesh of My Flesh… photo shoot here

From the song “Stop Being Greedy” from It’s Dark and Hell is Hot